The following article on the neoliberalisation of education in Sri Lanka was published in the Sunday Island on Jan 15th, the Sunday issue of a popular English daily in Sri Lanka. This article which is the third I have written on neoliberalism was also written in the context of strike action on Jan 17th by the Federation of University Teachers Association (FUTA) opposing the Government’s privatisation of higher education bill. With mounting protests the Government has shelved the bill for now. On the other hand, the situation in Sri Lanka is at one level no different from the kind of budget cuts facing CUNY.

—

Dispossession of Education and Youth Indebtedness

By Ahilan Kadirgamar

One of the strongest pillars of our society is again under attack by the State. Generations of educationists, concerned parents, students and the broader citizenry contributed towards building a solid free education system, and the foundation they laid has withstood major insurrections, counter repression, civil war and economic crises. And now, given the post-war opportunity for social development, public investment in education should be aggressively increased to build on that legacy. However, the Rajapaksa regime is on the short-sighted and socially devastating path to end free education. Neoliberal privatisation of education, which I will address here, is being pushed by states around the world in the interest of finance capital. It is ironic that while it is the economic crisis that is blamed in the Western world for budget cuts and the neoliberalisation of education, in Sri Lanka the assault on education is thrust forward with the false promise of a prosperous economic future.

Ending Free Education

“Four regulatory and monitoring bodies will be established under the proposed Quality Assurance, Accreditation and Qualification Framework Act to monitor and regulate private degree-awarding institutions, private universities and academies…” claimed a news item earlier this week. It went on to quote the Higher Education Ministry Secretary, Sunil Navaratne, who said that “ these monitoring bodies would oversee degree programmes, time allocated for degree and diploma programmes, the time allocated to lectures, the qualifications of the academic staff, the recruiting policies and minimum qualifications required for degree and diploma programmes” and continued, “private higher educational institutes have been registered under the Department of Registration of Companies or under the BOI or both as private establishments. But there is no proper monitoring system…”

The act mentioned above is what others are calling the privatisation of higher education bill, and it is a bad omen for what is in store for educational policy in the coming months. The Secretary’s comments are deeply worrying for a number of reasons. First, it raises concerns about the future of academic freedom with vast powers given to the Ministry of Higher Education. Second, free education is looking to come under attack with public education cannibalised by private education. Third, the encroachment of businesses and companies into education over the past decade, rather than being curtailed or abolished, are now to be regularised. In other words, this attack on free education is going to mould the educational system with a business mind-set. The Secretary’s interview is not an aberration but reflects a much larger project at work towards privatising education. While another news item claimed that the privatisation bill has been shelved for the moment at the recent Cabinet meeting, if one is to learn from the manner in which the anti-democratic 18th Amendment was eventually passed after some dithering in 2010, one should expect the Rajapaksa regime to push this bill forward in the near future.

The process of change expected from recent Government pronouncements is very similar to the World Bank report of July 2009, available on their website and titled, ‘The Towers of Learning: Performance, Peril and Promise of Higher Education in Sri Lanka’. Much like the Secretary, the World Bank also speaks of “National Qualification Frameworks”, “quality assurance” and “accreditation”. It also discusses the challenges of planning and financing higher education. While it rightly calls for an increase in government expenditure, the main thrust is towards public-private partnerships; with the government subsidising educational businesses. The World Bank report also discusses the issues of unemployment facing our graduates, but the solutions it proposes are no guarantees for employment creation. Specifically, it is uncertain how adopting a business model of education will increase employment. There is no clear link between privatising education and a rise in employment opportunities. For then, how does one account for the increasing unemployment in the Western economies whose educational system the World Bank would like us to emulate?

This thrust of the World Bank’s approach was also echoed in the annual report of the Central Bank for 2010, released mid-year 2011. In fact, the Central Bank report even used the language of financing through the commodification of education: “Entrepreneurial orientation of university education is another possible avenue for alternative financing as well as attracting foreign students from other countries.” Indeed, the Rajapaksa regime does not seem to have a vision for the economy other than making the country and our society entirely dependent on tourism, which now may be extending to foreign students and educational tourism.

The Neoliberal Logic of Privatising Education

Ending free education through a major push to privatise education has thus been in the works over the last three years if not longer. It is my contention, that the post-war period and the second term of President Rajapaksa have opened worrying possibilities of neoliberalising education as part of a second wave of neoliberalism coming after the first wave under the Jayawardene regime. The last two budgets and the annual reports of the Central Bank reflect this second wave of neoliberalism supported by global finance capital and neoliberal institutions such as the IMF and World Bank. While I have discussed this second wave of neoliberalism and the neoliberal budget in the past, I would like to discuss here some specific concerns as they relate to the neoliberalisation of education.

I must first acknowledge some issues intrinsic to education and the educational system, which many veteran academics and activist intellectuals have already addressed. For example, several academics have pointed to the dangers of the increasing militarisation of education undermining academic freedom. Others have articulated aspects of social values, democratisation and our sense of freedom from the time of Independence that is tied to the egalitarian ethos endemic to free education. The various interventions by the Federation of University Teachers Associations (FUTA) and the seminar organised last week at the University of Colombo by the University Teachers for Democracy and Dialogue (UT4DD) reflect a range of important views on privatising education.

My point is about the political economic aspects related to the neoliberal logic of privatising education. This process of privatisation exploits the economically weaker sections of society through “accumulation by dispossession”; where education costs are borne by the poor through increasing indebtedness in order for educational businesses to flourish and global capital to accumulate. If we are to learn from the failure of educational policies in the West, the major lesson is that the cuts in public funding towards education and a business mind-set have devastated the economic and social life of recent generations of youth. In fact, the establishment-leaning Economist magazine itself recently claimed that student loans in the US are exceeding US$ 1 trillion. Such debt has crippled the economic future of millions of youth, as they are unlikely to find jobs to pay back such enormous loans. Furthermore, increasing income inequalities over the last few decades of the tenure of neoliberalism have further aggravated their economic situation.

Now, one of the World Bank report’s recommendations for Sri Lanka claims: “Private HEIs [Higher Education Institution] charge fees which could make it difficult for gifted students from poor homes to access their services. This can be overcome by policies to provide talented poor students with student aid, such as vouchers, scholarships, bursaries and loans.” In fact, such a move could severely indebt our youth and poorer families could lose even their meagre assets and homes in the hope of educating their children for a better future. Thus the Rajapaksa regime’s move to privatise education is not only a betrayal of the State’s so-called social contract to meet the costs of reproducing society, but also a capitulation to the interests of global finance capital preying on the rural and urban masses.

Demands and Protests

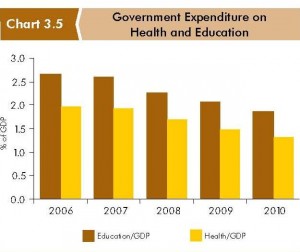

In this dire context, strike action by FUTA last year and particularly their demand calling for government expenditure on education equivalent to 6% of GDP was a welcome move. In fact, government expenditure on education has fallen steadily between 2006 and 2010 from 2.7% down to 1.9% of GDP. In 2010, budgetary expenditure on education was a mere 7.3% compared to the 14.9% average for South Asia. Both as a proportion of GDP and of the Budget, Sri Lanka by far spends the least on education in South Asia, and competes with lowest spenders in the world. Indeed, even the World Bank report claims that: “Countries such as South Korea, Malaysia and Thailand, whose economic performance is of interest for Sri Lankan policy, invest over four percent of GDP and between 15 and 28 percent of Government expenditures on education.”

source: Central Bank Annual Report 2010

source: Central Bank Annual Report 2010

Given the post-war priorities of social reconstruction, a serious commitment towards education calls for major increases in the educational budget and similar decreases for example in the defence budget. However, the timely and forthright FUTA demand of 6% of GDP for education cannot stand on its own. Teachers and students will have to unite with other sections of society facing dispossession. Changing the structure of the economy to accommodate social welfare will have to come hand in hand with struggles for democracy to challenge the authoritarian neoliberal bent of the Rajapaksa regime. Furthermore, engaging the economic problems in Sri Lanka should involve understanding the global context, particularly as forces shaping economic policies are global as much as they are national.

Over the last year, there have been mounting protests and even riots by students, in Greece, US, UK and a number of other countries. Those protests have as much to do with neoliberal dispossession of education, as the protests by university students here in the context of the privatisation bill. And militarised policing in those countries have been as much a part of repression as have the recent incidents in our national universities. In the context of the State demonising students protesting at the barricades, the least we can do is show solidarity and voice our protest against the privatisation bill that will dispossess education and throw our youth into life-long indebtedness.