The following article on the prison uprising ten days ago in Sri Lanka was published in the Sunday Island on February 5th, the Sunday issue of a popular English daily in Sri Lanka.

The recent uprising at the Welikada Prison in Colombo should at a minimum lead to deeper introspection about the character of State institutions and the ideological and political foundations of our society. Unfortunately, public discussions on the uprising of January 24th for the most part have been appalling, characterised by rumour and prejudice rather than careful reporting and reflection. I do not claim to know the immediate causes of the prison uprising. Media reports suggest that thousands of prisoners protested prison conditions, leading to clashes where scores of prisoners and a few prison guards were injured, and that the uprising was squashed with tear gas and firing by the police and the military. It will, however, take engaged research interviewing the prisoners themselves to document the uprising accurately.

All I intend to do here is raise larger political, economic and social questions that we should be discussing and debating given the uprising by this marginalised section of society. I believe this uprising is neither an aberration nor limited to the conditions in the prisons, but reflective of the historical short comings of the criminal justice system as well as worrying political economic trends at the current moment.

Prison Conditions and Reactions to the Uprising

I want to begin by quoting an excellent report authored by former Commissioner-General of Prisons, H G Dharmadasa titled ‘Rights of Prisoners’ in Sri Lanka State of Human Rights 2003 published by the Law and Society Trust:

“During its visit to Welikada prison in February 2003, the premier penal institution in the country, the research team found the conditions deplorable, especially in the remand section. The prison has an authorized capacity of 1,500 prisoners, but was holding nearly 4,000. Welikada prison, which is the designated prison for first offender convicts, was also holding a large number of remand prisoners due to overcrowding of remand prisons. … During the research team’s visit, which was in the morning, hundreds of inmates were lying on the floor with nothing to do. The building, a part of the old colonial structure, was in a very bad state of disrepair. Inmates and officers informed us that the roof leaks during the rainy season, flooding the floors. The walls were so dirty that it was not possible to see any paint on them. … The lack of ventilation in the entire building created a suffocating atmosphere. The small openings in the cells that passed off for windows did not permit sufficient inflow of fresh air. The situation was made worse by severe overcrowding. The odour and heat emanating from unkempt human bodies and the filthy surrounding were overwhelming. Cells and corridors were infested with bugs and cockroaches. … Prisoners also complained of inadequate water for both drinking and washing. As running water was available for only a short period each day, prisoners had to collect water in plastic containers. Bathing facilities were scarce. … There were only eight functioning toilets for the entire population of 1,400 prisoners – that is, one lavatory for 175 people. It was also very apparent the remand prisoners did not have sufficient facilities to cut their hair or shave.”

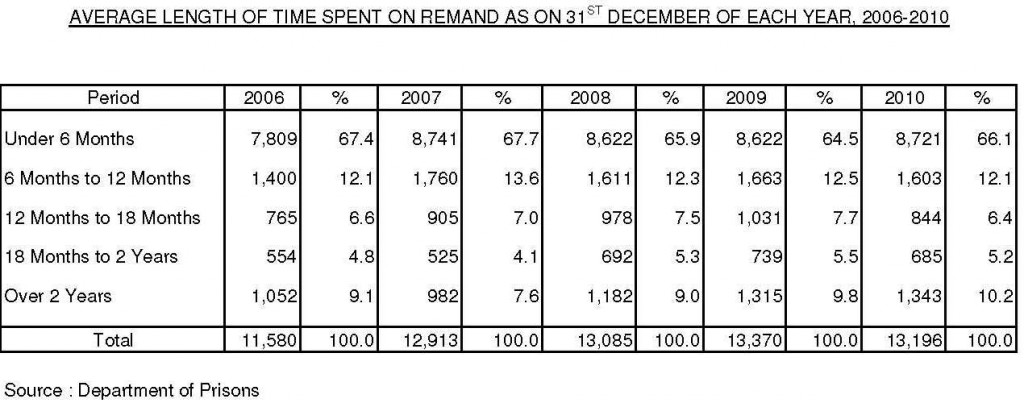

This report written a decade ago is also reflective of conditions in many of the prisons today. An IPS article by Ranmali Bandarage on 20th July 2011, describes similar horrendous conditions and overcrowding in the female ward of the Welikada prison, informing us of state negligence and miserable treatment meted out to incarcerated women. This report on prison conditions and human rights parallels decades of painstaking legal analysis challenging repressive laws by the Civil Rights Movement and sustained documentation of police brutality and torture by the Asian Human Rights Commission.  The systemic failure of the overstretched criminal justice system together with the scandal of lawyers, judges, the police and the Attorney General’s department colluding in endless deferrals of court proceedings, results in people being held in remand for months if not years without being convicted. Department of Prisons data on remand prisoners show that over a third are incarcerated for over six months and almost 10% for over two years.

The systemic failure of the overstretched criminal justice system together with the scandal of lawyers, judges, the police and the Attorney General’s department colluding in endless deferrals of court proceedings, results in people being held in remand for months if not years without being convicted. Department of Prisons data on remand prisoners show that over a third are incarcerated for over six months and almost 10% for over two years.

Welikada prison is also etched in Tamil political memory as the site of the most vicious murder of 35 and then 18 Tamil political prisoners on 25th and 27th July 1983. Last week, the Tamil press was concerned about the possible repetition of a massacre of Tamil prisoners. The Tamil press in seeing the uprising through an ethnic lens failed to grasp its politics. In any event, the State was quick to dissociate any links with Tamil prisoners on remand and moved them immediately to a different prison. While the incarceration of political prisoners, including of presidential candidate General Sarath Fonseka, exposes the State’s direct assault on democratic rights, there is a systemic logic to criminalisation, custody and incarceration of all people which relates to the legitimacy and brutality of the State. In this context, some analysts have rightly made connections between the prison uprising and the burst of protests in recent weeks, including those by students, university teachers and trade unions. They claim such protests are reflective of challenges to the legitimacy of the State and the militarised authoritarianism of the ruling regime

Subaltern Classes and the Criminal Justice System

Despite some interventions that attempt to contextualise and understand the prison uprising, the dominant response in the public sphere has been unsympathetic if not simply condemnatory. I would like to focus next on the reasons for such callous reactions and their implications, especially how they contribute towards reinforcing repressive ideological, legal and militarised policing trends.

The bulk of the people imprisoned belong to what are called the subaltern classes. Those are classes that are structurally excluded by state services and the capitalist system, and are seen to be expendable by the broader society towards prolonged incarceration, police brutality and repression. Even the Left failed to support these classes historically, labelling them “lumpen” elements, as they were not seen to be part of the “working class”.

The bulk of the people imprisoned belong to what are called the subaltern classes. Those are classes that are structurally excluded by state services and the capitalist system, and are seen to be expendable by the broader society towards prolonged incarceration, police brutality and repression. Even the Left failed to support these classes historically, labelling them “lumpen” elements, as they were not seen to be part of the “working class”.

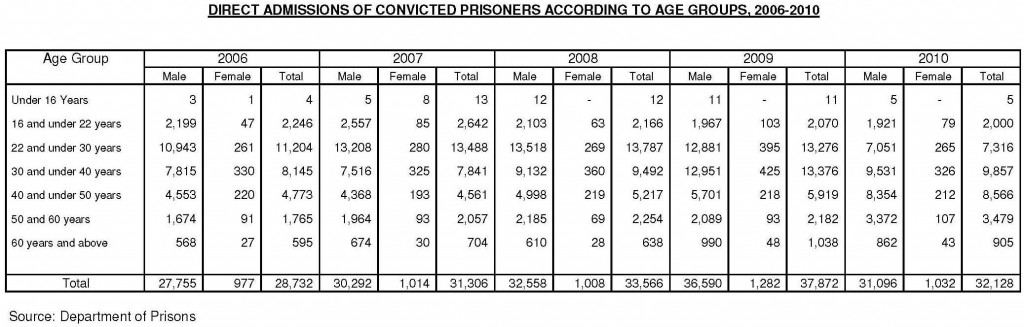

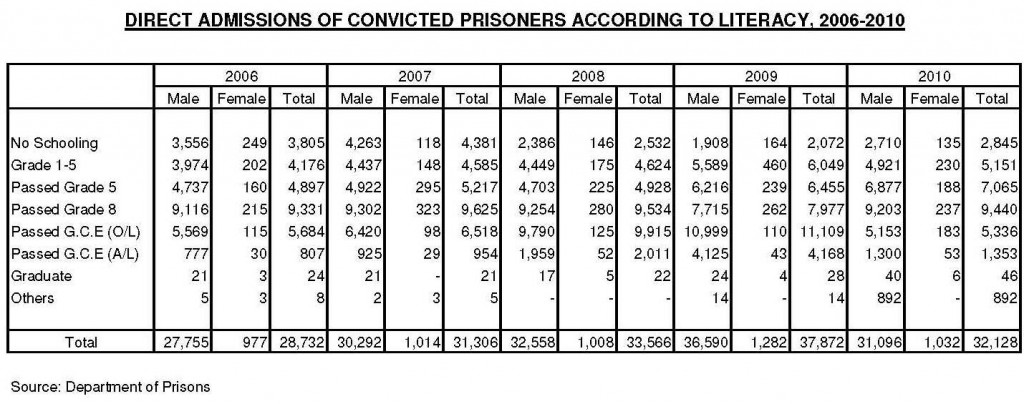

The Department of Prisons data shows that of those convicted between 2006 and 2010, the bulk are men between the ages of 16 and 40 who either had no education, primary education or have only passed Grade 8. The numbers of prisoners who have passed O/L and A/L are relatively fewer in most years. It is no coincidence that unemployment is also highest for these men. Thus illiteracy, unemployment and economic exclusion are some facets of subaltern classes.

Such social and economic marginalisation of the subaltern classes is also extended to forms of social exclusion, particularly those seen to be socially deviant, thus ideologically and legally constructing what is normal and abnormal. For example, the repression of sexual minorities and sex workers is justified by social prejudice. Our penal code criminalises same-sex orientation, sex work and abortion. This is where modern law, our colonial inheritance, encroaches deeper into society and is instrumental in both criminalising certain forms of social behaviour and physically banishing sections of our population through incarceration. While Sri Lanka is particularly regressive on legality relating to sexualities, this tension between modern law and the rights of its citizens is common to all so-called liberal democratic states.

The ideological labelling of certain social groups as social enemies combined with state sanction of social exclusion through the criminal justice system is a slippery slope for any liberal democracy. The escalation of which combined with extreme forms of militarised state brutality can lead to fascism. Indeed, Nazi Germany was the exemplar of imprisoning and executing not just Jews, but also Gypsies and homosexuals, who were all considered to be social enemies. This is where acts of intolerance and attacks in the media on sex workers, sexual minorities and women seeking abortion, the subaltern classes including the incarcerated are early signs of reactionary conservatism if not cultural fascism threatening our democratic political culture which we must challenge at the outset. Furthermore, the modern powers of the law, police, prisons, military and the state more generally have to be challenged if they are to be kept in check, and that is where the recent protests and the prison uprising gain significance as forms of radical democratic resistance that we must support.

Neoliberal Policies and Incarceration

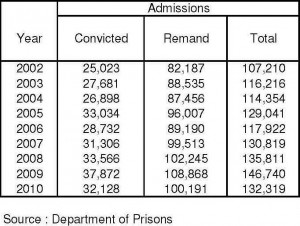

Returning to the issue of overcrowding prisons, the data for 2002 to 2010 shows an increasing trend in the number of people admitted to prison each year from 107,000 in 2002 to 132,000 in 2010 after a peak of 147,000 in 2009. This is a worrying trend which parallels the increasing inequality in our society and relatively decreasing state expenditure on education and health. Many have found this to be a trend common in other countries similarly pursuing neoliberal economic policies; where inequality rises, state services are reduced, poverty increases often leading to thefts, petty crimes but also protests, and the state responds with repression and increasing incarceration. The elite who manipulate the law and the business tycoons that devastate the economy through greed and speculation are of course rarely touched by the repressive arm of the state.

Returning to the issue of overcrowding prisons, the data for 2002 to 2010 shows an increasing trend in the number of people admitted to prison each year from 107,000 in 2002 to 132,000 in 2010 after a peak of 147,000 in 2009. This is a worrying trend which parallels the increasing inequality in our society and relatively decreasing state expenditure on education and health. Many have found this to be a trend common in other countries similarly pursuing neoliberal economic policies; where inequality rises, state services are reduced, poverty increases often leading to thefts, petty crimes but also protests, and the state responds with repression and increasing incarceration. The elite who manipulate the law and the business tycoons that devastate the economy through greed and speculation are of course rarely touched by the repressive arm of the state.

The solution – a reminder to those in our neoliberal establishment now promoting privatisation of higher education and financialisation of the economy – does not lie in emulating the US which spends considerably on prisons and policing. Indeed, the racialised neoliberal US economy has led to increasing unemployment and incarceration of young black men; unemployment among blacks is twice the already high unemployment rate of whites and data from 2007 shows a horrendous statistic of one in every nine black men between the age of 20 and 34 incarcerated that year. Radical black intellectuals Angela Davis and Ruth Gilmore have shown how incarceration, militarization, economic dispossession and dehumanisation work in tandem and in turn the importance of a vision to abolish prisons. What we can we learn from the US experience is that sections of the black population, much like our subaltern classes are subject to social exclusion and oppression regardless of economic prosperity. The urgent need in Sri Lanka as in the US is to reverse the damage already done by neoliberal policies, militarised policing and incarceration.

The prison uprising is thus a wakeup call. It should alert us to the predicament of the subaltern classes and the socially excluded, rethink our public engagement and eschew our social prejudices. For that we must begin with the recognition of the historical oppression of the subaltern classes, whether it is their expulsion from society through incarceration or their dispossession in our rural and urban economies. The question now is whether we have the humility to listen to the prisoners’ cry to begin discussing and debating the political, economic and social deterioration of our society.

The prison uprising is thus a wakeup call. It should alert us to the predicament of the subaltern classes and the socially excluded, rethink our public engagement and eschew our social prejudices. For that we must begin with the recognition of the historical oppression of the subaltern classes, whether it is their expulsion from society through incarceration or their dispossession in our rural and urban economies. The question now is whether we have the humility to listen to the prisoners’ cry to begin discussing and debating the political, economic and social deterioration of our society.